Cesarean Tubal Ligation

|

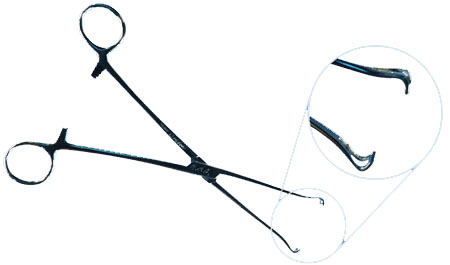

| A babcock. Notice that it is made to hold a tubular organ without crushing the tissue. |

Miserable, I held the babcock in space, wondering what I should do. Should I speak up? I didn't feel empowered and didn't want to be disliked. Was this remote and unwilling enough for me to be quiet and save face? Would speaking up be making a selfish scene? Remember, the patient is awake for a cesarean section; it's sort of too late to discuss ethics, especially when this patient has chosen to do the objectionable thing. But this is grave matter! And I know it to be grave matter! And I am doing it anyway!!

|

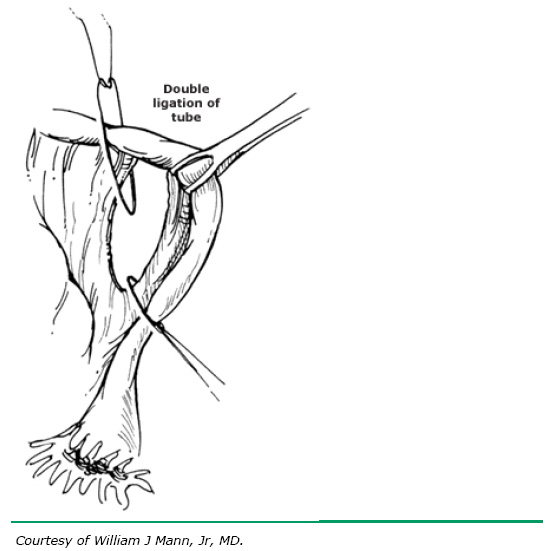

| The babcock is at 2 o'clock in this picture. The other two things are strings being tied around the tube. The strings are clipped and the tube between them is removed. |

CCC 1857: For a sin to be mortal, three conditions must together be met: "Mortal sin is sin whose object is grave matter and which is also committed with full knowledge and deliberate consent."It was over before my analysis was over. So I said nothing. I still didn't cut the sutures. I went to confession before receiving communion. The conclusion of the priest was that this was remote and not "deliberate consent" enough to constitute mortal sin, but I was very, very determined not to let this happen again. It was careless not to say anything to the attending. I did better in the past, when I spoke up discreetly before a mirena insertion. But this wasn't the worst thing that happened.

Birth Control on an Away Rotation

Fourth-year med students occasionally spend weeks at a time at other med schools or residency programs. These "aways" are often done to make a positive impression on the residency program there and are called "auditions" in that case.

I was doing an audition rotation at a school and got waaay too close to prescribing contraceptives. I didn't realize that the clinic would be so pro-birth control, but I found more than 75% of the patients taking some form of hormonal birth control, and a strong culture supporting "safe sex" with 100% condom usage. I was at a loss.

I was doing an audition rotation at a school and got waaay too close to prescribing contraceptives. I didn't realize that the clinic would be so pro-birth control, but I found more than 75% of the patients taking some form of hormonal birth control, and a strong culture supporting "safe sex" with 100% condom usage. I was at a loss.

I was on a month-long rotation trying to get people to like me. Med students are always sent into the room first; if I go in first and share all my contraception-why-not knowledge and then the attending goes in, the patient will ask one of two things: "So, is that med student just crazy?" or "Have you been lying to me, doc?" Worse, the patient will decide not to use contraceptives (yay), the attending will ask why (uh-oh), and the patient will explain that "the med student said...," and the attending will (annoyed) have to re-explain all the falsehoods and (red alert) rebuke the med student.

| (Nexplanon) |

You might argue that this course of action might have been good: it might have created a chance for me to bravely say, "Well, Dr. X, I was actually reading a paper that says (insert pro-family stuff here)...." But I expect those things would fall on deaf ears of the highly experienced, academic, and culturally blinded physicians I was working with. Worse still, I would have confused patients, possibly discredited the arguments against contraception, and possibly eroded their relationship with their physician.

So I clammed up and tried to say true things and not recommend contraception. I tried not to be excited when people were sexually active and using condoms and birth control. I tried to encourage people to think about whether they wanted to be pregnant and let that inform their decision to have sex. I was about the only one in the clinic to continuously tell teens that the most effective way to avoid pregnancy was to avoid sex.

But I began to echo my attendings' speeches and advice about birth control as I counseled women about "the options," which was a requirement. I was at fault for not knowing enough numbers to give to patients myself, though. I seemed to morph into someone who was pro-birth control: it decreases the risk of ovarian cancer and uterine cancer, I'd say, and the only side effect is possible irregular periods. When people asked me about future fertility, I said that "our professional organization [ACOG] instructs us that future fertility is not affected." (That was the most painful thing.) Working twelve-hour days in this place for four weeks wore down my defenses.

The ultimate result was the day I was almost running the adolescent medicine clinic and writing notes and plans (only missing the formality of writing the script and signing it) that included birth control of all flavors. After that, I found myself crying in a confessional again. This time, although the priest never said "that was a mortal sin," he did extract a firm purpose of amendment and my intention to say the penance. And he did tell me that I, like pharmacists, lawyers, and some others, stand in danger of losing my soul in my profession. It sounds harsh, but as I knelt in the confessional I felt and knew that he was very, terrifyingly correct.

So, Catholic medical student: discreetly inform your intern/upper-level/attending/preceptor/whoever. If it's too late, you are allowed to say something like, "Oh, I prefer to just observe; I'm happy to explain afterwards." And if you get into a sticky long- but short-term situation like my away, you need to do a little research (I'm hoping to put something up here with quick facts on contraceptives, etc) and be unafraid. Don't break up doctor-patient relationships, but do offer an alternative. I'll share a positive story in the a next post (because I have one).

No comments:

Post a Comment